Hamilton, Ontario (1937)

The Building:

Post Office, Customs House and Federal Government edifice built as a works project during the Great Depression. Many such grand art deco buildings were built across Canada during that period.

Project Synopsis:

Floor to ceiling marble cladding designed to look like ashlar with mortar joints created using a contracting color of marble was threatening to become detached from the walls of this impressive single room. Vibration from a great increase in traffic volume, combined with a huge project to repurpose the rest of the building, left the 1” X 16” X 48” marble slabs in a precarious condition. It could not be determined which pieces were sound and which were being held by friction with their neighbors.

One plan suggested by the masonry contractors was to dismantle and reinstall the marble. HPCS was asked for an opinion on this idea, and at the same time, to suggest and develop a method of establishing a measurable improvement to the conditions without removing the marble.

What was wrong with removing the marble and re-applying it with a modern epoxy?

Possibly nothing and possibly everything. The risk of not getting it right and of doing a great deal of damage in the process was very high. The narrow bands of dark marble that simulated joints were thoroughly fractured and would have completely disintegrated during removal. HPCS cautioned against removal for this reason. Always preferring a minimal intervention conservation approach, we investigated the nature of the delamination problem.

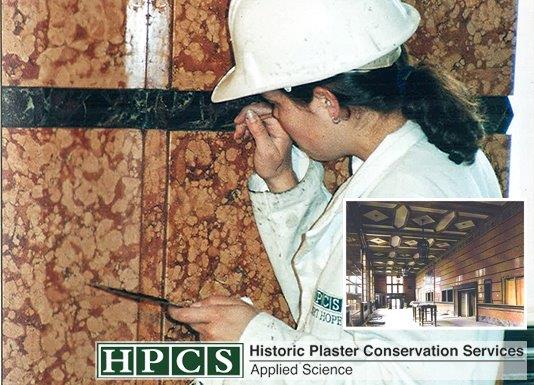

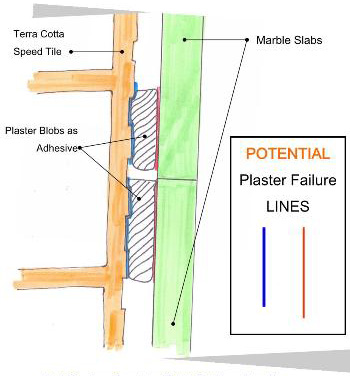

Marble cladding is held on terra cotta walls by daubs of plaster of Paris. Each panel would have had four or six daubs applied to the back side and would then have been pressed into a predetermined location on the wall with stops in place to regulate the precise location of the panel.

This is high-skilled work requiring a team following a well-established routine to get the fine result we were dealing with. Disturbing it further would be a very last resort.

Confirmation of delamination can be done with a rubber mallet, by sounding as it were, to determine that there is an un-acceptable vibration – a “cracked china” sound rather than a dull thud. However, sounding with a rubber mallet doesn’t tell us anything about the location of the disengagement. We needed some real science.

The non-destructive examination method we selected for this project was Ground Penetrating Radar, supplied to us in a neat package by GPR Geophysics International.

The full story is in our Documents Library in a paper entitled Marble Conservation at the Dominion Public Building.

The point we make here is that the best conservation is a minimal intervention affair. We are always risk averse when it comes to the historic fabric we are responsible for. Whenever possible, we do everything we can to avoid dismantling historic fabric. This fundamental principle challenges us to find better, less intrusive ways of addressing the many different conservation issues we encounter.