Annandale House National Historic Site

Tilsonburg, Ontario (1880)

About the Building:

With its magnificent interior, Annandale House serves as a monument to the Victorian style of design, known as the “Aesthetic Art Movement”. Popularized by Oscar Wilde, this movement promoted the use of colour and decorative detailing in all areas of the home. From extravagant, hand-painted ceilings and elaborate inlaid floors to ornate mantles, hinges and stained glass, Annandale House combines the best of what the Aesthetes professed.

Built by Edward Tillson, the first Mayor of Tillsonburg, the building has been restored to its former glory. With a newer addition designed by the firm +VG Architects, the complex now serves the community as a museum and tourist information centre.

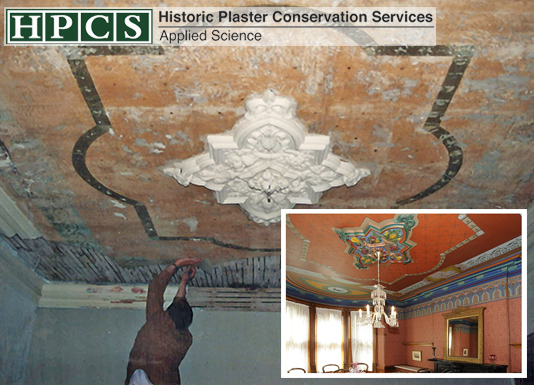

Restoring the Period Rooms

The building’s significance is based on the high quality of original painted decoration on plaster ceilings in the period rooms. HPCS was responsible for all aspects of plaster and paint finishes conservation. After conducting a feasibility study that included testing and recording, we supervised the plaster replacement where it had been previously removed. After consolidation of the plaster, we retained the services of the late Andrew Kwiecinski, a talented graduate of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, for the conservation of the interior paint finishes. The project ran to a successful completion over a four-year period, with full approval and financial contribution from the Heritage Branch of the Ontario provincial government. Following the restoration, the building received a National Historic Site Designation.

In almost all stages of the Annandale Project, a three-step process was followed:

- Assessment of the plaster condition by HPCS

- Plaster consolidation and repair as needed to ensure permanent stability

- Conservation of paintings by Andrew Kwiecinski.

A Costly Lesson Learned

This process deviated somewhat in 2005 when the last unfinished room on the second floor was cleaned and fully repainted without plaster consolidation or any other serious treatment. Apparently, a local handyman had been hired to do some cheap cosmetic repairs using flat washers hidden by drywall compound. He then led the museum folks to believe that the ceiling was safe and sound. On his advice, and unaware of the hidden treatment he had applied, the museum proceeded with the expensive process of conservation painting the ceiling. In 2011, HPCS was called in to discover that a grand piano sized section of the beautiful ceiling had collapsed, with the remainder of the plaster in a very tenuous state. The ceiling was ultimately consolidated; new plaster was placed where the collapse had occurred; and the ceiling was again painted at considerable expense.

In summary, the museum had paid for a poor quality repair; paid for a high quality conservation painting; suffered the ceiling collapse; paid for new plaster to replace the collapsed plaster; paid for the consolidation treatment provided by HPCS; and paid again for a redo of the conservation painting. Suffice it to say that a costly lesson was learned.